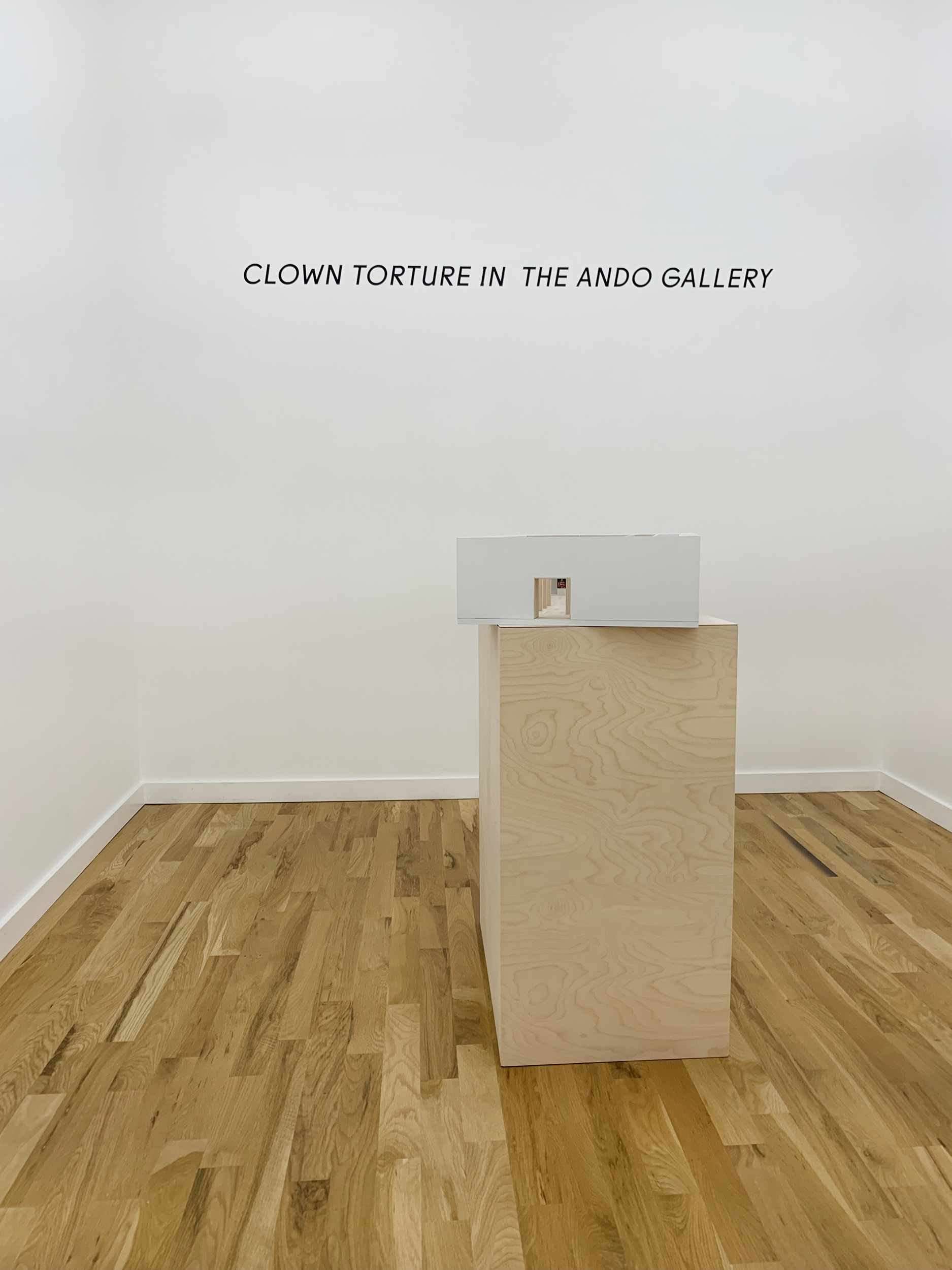

All of the galleries within The Art Institute of Chicago are numbered. Gallery 109 was designed by the revered Japanese architect Tadao Ando (b. 1941), and was his first project in the United States. Known now as “The Ando Gallery”, the room, which opened to the public in 1992, is lauded for its sensitivity to space and form.

The lighting in the Ando Gallery is kept dim, nearly dark. The space is rectangular and contains two long walls of glass behind which are displayed painted screens and earthenware vessels. Just within the entrance to the gallery stand 16 free-standing wood columns: a reductivist forest that separates the contents of Gallery 109 from the rest of the Museum. The room is serene, inviting reverence and quiet contemplation—of the works on display and of the room itself. Many find the Ando Gallery romantic. Guards have been known to espy frequent coupling. First base. Second. Third. Etc.

Clown Torture, an artwork from 1987 by American artist Bruce Nauman (also b. 1941), consists of five narrative sequences of clowns behaving, well, clown-like. The work is displayed on four color video monitors (two of them turned on their side) and two video projections on facing walls. The work is intended to be seen in an enclosed darkened space. When the Modern Wing opened in 2009, Clown Torture had pride of place on the second floor. I don’t think anyone ever fucked in the gallery.

The narrative pieces in Clown Torture play in a perpetual loop, with each loop featuring a singular clown either trapped, harangued, flummoxed, or just downright bored. Portrayed by the actor Walter Stevens, the clowns are loud, messy, sloppy, and bossy—portraying the emotional equivalent of flatulence. One clown incessantly stamps his feet and screams “NO NO NO NO NO NO NO!” Another disastrously balances a glass bowl full of water against the ceiling with a broom handle. Of course it falls and breaks. Another clown sits in a toilet stall and passes the time sitting on the pot. Nauman’s written instructions are that the audio from the five sequences should be played very loud. Clowns, of course, entertain. Just like artists.

The Art Institute acquired Clown Torture in 1997, and it is a masterpiece. To wit, The Art Institute uses stills from the work on its way-finding signage within the museum: an indication of the seminal nature of Nauman’s achievement.

The Art Institute is no stranger to exhibition juxtapositions. In 1979, the conceptual artist Michael Asher relocated a 1917 cast of French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon’s 1788 original marble statue of George Washington which had been on display at the Museum’s Michigan Avenue entrance. Asher re-installed G.W. in Gallery 219 with other eighteenth-century European works: George being reunited with the Europe from which he sought to part company.

In September 2021, Barbara Kruger will be exhibiting her 1997 fiberglass statue Justice in the repository for The Art Institute’s 19th Century holdings: the sculpture court of the American Wing. Justice depicts two right wing mid-20th Century zealots, J Edgar Hoover and Roy Cohn, embracing and kissing. The location of the installation is unexpected and certain to titillate or startle, depending on one’s predisposition to such things.

Of course this proposal may be construed by some as architectural sacrilege. So be it. It is undeniable that the geometry of Clown Torture, it’s pedestals and monitors and it’s perpendicular projections, marry quite conveniently with Ando’s exhibition space. Depending on your proclivities, this proposal is either about the the elasticity of an institution’s collection and venue, or it is an exercise in judgement: bad, poor or punk.

Which leaves me here: When it comes to real estate, only three things matter: Location! Location! Location!

Or, let me put it another way: A clown walks into a bar. The bartender says, “What is this? Some sort of joke?”

–––––––––

Concept: Jason Pickleman

Research: Bianca Bova

Model: Andrew Jiang